What does risk really mean?

Why supposedly "safe" sectors may be nothing of the sort

Many investors are attracted to the perceived stability of certain sectors. But safety stems from the price you pay, not the underlying dynamics of the businesses you buy.

Defining defensives and cyclicals

Stock market investors group companies into sectors in order to gauge their likely performance at different times in the economic cycle. For example, producers of food & beverages and tobacco fall within consumer staples, a sector often called “defensive”. According to global asset manager Schroders, this is because demand for food, cigarettes, etc, typically remains stable regardless of the performance of the wider economy. Therefore, revenues and profits for these kinds of companies tend to hold up well, even if the broader economy is suffering a downturn.

As a result, these defensive companies are often perceived as safe, reliable investments. Such companies can be of particular interest to income investors as in general their stable profits often allow them to pay consistent dividends.

By contrast, Schroders says that “cyclical” sectors are those that perform best when the economic times are good but they tend to see demand fall away when the economy slows. They state autos and retailers as classic consumer cyclical sectors because people spend more when they are confident about the economic outlook. Materials and industrial stocks fall into the same bracket as companies invest more when they expect demand to rise.

However, the revenues and profits, and therefore share prices, of these cyclical companies can be volatile as demand ebbs and flows alongside the performance of the broader economy.

Schroders says that many investors make the error of equating this day-to-day share price volatility with risk. Risk, in investing terms, means the risk of permanently losing capital. Substantial research points to the fact that the price you pay is the key determinant of the returns you make. The most critical risk, therefore, is the risk of overpaying for an investment in the first place.

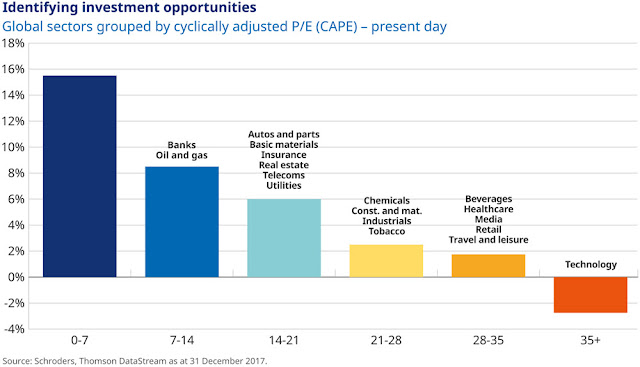

In the chart below, Schroders shows the returns you would historically have made on an investment, given the initial price paid. Buying stocks that are very cheap, up to 7x cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings (on the left hand side of the chart) has historically resulted in the greatest returns over the subsequent ten-year period. Meanwhile, buying stocks in the most expensive bracket, on the right, typically results in a loss.

The chart also shows which market sectors currently fall into which price-to-earnings bracket. After the global rally in equity markets over the past few years, there are no ultra-cheap sectors in the 0-7x bracket. According to Schroders, there are, however, several in the next two cheapest brackets and what is notable is that many of these are “risky” cyclical sectors, such as banks, basic materials and autos.

Schroders says the value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. References to sectors are for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation to buy and/or sell.

On the right hand side, technology falls into the most expensive bracket – the one that Schroders claims to typically see losses on a ten-year view. Then there are several sectors in the second most expensive bracket. Two of these – beverages and healthcare – are sectors typically perceived as defensive. But according to Schroders, it is their business models that are defensive, not their share prices. History suggests that investors in these sectors, at current prices, could be at risk of underperformance compared to other sectors.

Certainly some stocks are cheap for good reason and it is a difficult task to filter out those from the ones that are currently cheap but have scope for recovery. This is where the benefits of active stock picking come to the fore. Active investors willing to do the research are able to find companies within those unloved sectors that trade at attractive prices and have sufficient balance sheet strength to weather difficult periods.

This is not to say that stronger returns are guaranteed if you invest in the cheaper companies – there are no guarantees with equities, as their value can be volatile and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. It may take time, and considerable patience, for the market to appreciate a stock’s true value, which is why equity market investing is best suited to those able to take a long-term view.

Fund manager view - Andrew Evans, Equity Value, says:

“There are no equities that are always safe or always risky. There are only equities that are too cheap or too expensive. A business could have the most volatile earnings stream in the world but, if you buy it at a 90% discount to fair value, you are giving yourself a very good chance of making money from that investment.

“In the same way, you could identify the business that boasts the most stable earnings stream in history and yet, if you pay 10 times what it is worth, you are highly unlikely to make money. In fact you are more likely to end up losing money. To us, that is the definition of risk and it has nothing to do with the supposed predictability and stability of an asset – only the price you pay for it.”

Taking a total income approach

For investors seeking income, these are important considerations to take into account. The consistent dividends offered by healthcare, food and beverage companies are clearly attractive. However, Schroders says paying too high a price for stocks offering such dividends means you could miss out on capital growth or even suffer a loss.

One way of trying to mitigate this risk to capital is to take a “total income” approach. This involves taking into account the price paid for a stock, as well as the dividend. Investors following such as strategy will pay close attention not just to a stock’s current dividend but its ability to grow that dividend. In some instances, they may even own stocks that do not currently pay dividends but that are expected to do so in future.

Such an approach may not access the highest dividends today, but does allow for potential capital growth as well as the income from dividends.

The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Many investors are attracted to the perceived stability of certain sectors. But safety stems from the price you pay, not the underlying dynamics of the businesses you buy.

Defining defensives and cyclicals

Stock market investors group companies into sectors in order to gauge their likely performance at different times in the economic cycle. For example, producers of food & beverages and tobacco fall within consumer staples, a sector often called “defensive”. According to global asset manager Schroders, this is because demand for food, cigarettes, etc, typically remains stable regardless of the performance of the wider economy. Therefore, revenues and profits for these kinds of companies tend to hold up well, even if the broader economy is suffering a downturn.

As a result, these defensive companies are often perceived as safe, reliable investments. Such companies can be of particular interest to income investors as in general their stable profits often allow them to pay consistent dividends.

By contrast, Schroders says that “cyclical” sectors are those that perform best when the economic times are good but they tend to see demand fall away when the economy slows. They state autos and retailers as classic consumer cyclical sectors because people spend more when they are confident about the economic outlook. Materials and industrial stocks fall into the same bracket as companies invest more when they expect demand to rise.

However, the revenues and profits, and therefore share prices, of these cyclical companies can be volatile as demand ebbs and flows alongside the performance of the broader economy.

Schroders says that many investors make the error of equating this day-to-day share price volatility with risk. Risk, in investing terms, means the risk of permanently losing capital. Substantial research points to the fact that the price you pay is the key determinant of the returns you make. The most critical risk, therefore, is the risk of overpaying for an investment in the first place.

In the chart below, Schroders shows the returns you would historically have made on an investment, given the initial price paid. Buying stocks that are very cheap, up to 7x cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings (on the left hand side of the chart) has historically resulted in the greatest returns over the subsequent ten-year period. Meanwhile, buying stocks in the most expensive bracket, on the right, typically results in a loss.

The chart also shows which market sectors currently fall into which price-to-earnings bracket. After the global rally in equity markets over the past few years, there are no ultra-cheap sectors in the 0-7x bracket. According to Schroders, there are, however, several in the next two cheapest brackets and what is notable is that many of these are “risky” cyclical sectors, such as banks, basic materials and autos.

Schroders says the value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. References to sectors are for illustrative purposes only and not a recommendation to buy and/or sell.

On the right hand side, technology falls into the most expensive bracket – the one that Schroders claims to typically see losses on a ten-year view. Then there are several sectors in the second most expensive bracket. Two of these – beverages and healthcare – are sectors typically perceived as defensive. But according to Schroders, it is their business models that are defensive, not their share prices. History suggests that investors in these sectors, at current prices, could be at risk of underperformance compared to other sectors.

Certainly some stocks are cheap for good reason and it is a difficult task to filter out those from the ones that are currently cheap but have scope for recovery. This is where the benefits of active stock picking come to the fore. Active investors willing to do the research are able to find companies within those unloved sectors that trade at attractive prices and have sufficient balance sheet strength to weather difficult periods.

This is not to say that stronger returns are guaranteed if you invest in the cheaper companies – there are no guarantees with equities, as their value can be volatile and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. It may take time, and considerable patience, for the market to appreciate a stock’s true value, which is why equity market investing is best suited to those able to take a long-term view.

Fund manager view - Andrew Evans, Equity Value, says:

“There are no equities that are always safe or always risky. There are only equities that are too cheap or too expensive. A business could have the most volatile earnings stream in the world but, if you buy it at a 90% discount to fair value, you are giving yourself a very good chance of making money from that investment.

“In the same way, you could identify the business that boasts the most stable earnings stream in history and yet, if you pay 10 times what it is worth, you are highly unlikely to make money. In fact you are more likely to end up losing money. To us, that is the definition of risk and it has nothing to do with the supposed predictability and stability of an asset – only the price you pay for it.”

Taking a total income approach

For investors seeking income, these are important considerations to take into account. The consistent dividends offered by healthcare, food and beverage companies are clearly attractive. However, Schroders says paying too high a price for stocks offering such dividends means you could miss out on capital growth or even suffer a loss.

One way of trying to mitigate this risk to capital is to take a “total income” approach. This involves taking into account the price paid for a stock, as well as the dividend. Investors following such as strategy will pay close attention not just to a stock’s current dividend but its ability to grow that dividend. In some instances, they may even own stocks that do not currently pay dividends but that are expected to do so in future.

Such an approach may not access the highest dividends today, but does allow for potential capital growth as well as the income from dividends.

The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Comments

Post a Comment